There comes a point each spring when the buds of a bullpen revolution seem to be everywhere. One team's closer competition between two great relievers inspires a managerial pledge to "play matchups" and get both pitchers saves. Another team's "fluid" situation suggests a possible closer by committee. A surplus starter might be used in a hybrid role, pitching long relief and high-leverage like the firemen of yore. And the memories of the previous October -- when some team probably got knocked out because it held its closer back for a save situation that never came; or when some team's dominant closer undoubtedly nailed a series of five- and six-out saves to become a legend -- encourage all of us to imagine the possibilities of a less restrained bullpen ace.

And then, the regular season -- and the exhausting demands of reality -- hits. We realize how hard it is to run an experiment in the middle of a season. Everybody mostly falls in line.

With nearly a quarter of the season complete, it's a good time to check in on the offseason and spring training hopes that the revolution might, finally, this time be nigh. Here's a State of the Bullpen in 2017: All 30 teams, ordered by loyalty to convention so far.

1. Cubs

Oh, that kooky Joe Maddon. Nothing he won't try, no unconventional strategy he won't employ. Like, check my dude out: Maddon's closer, Wade Davis, hasn't appeared in a game before the ninth inning all season. When the score is tied and Maddon is on the road, he goes to a series of setup men before bringing in his best reliever, who hasn't been asked to get more than three outs in a game yet. Nobody else on the roster has a save, while Davis has done basically nothing but get saves, in the most conventional way possible.

Oh, that kooky Joe Maddon. Nothing he won't try, no unconventional strategy he won't employ. Like, check my dude out: Maddon's closer, Wade Davis, hasn't appeared in a game before the ninth inning all season. When the score is tied and Maddon is on the road, he goes to a series of setup men before bringing in his best reliever, who hasn't been asked to get more than three outs in a game yet. Nobody else on the roster has a save, while Davis has done basically nothing but get saves, in the most conventional way possible.

This might surprise you, because Joe Maddon. But Maddon did this with infield shifts, too: He was at the cutting edge of extreme infield defense, the manager most responsible for turning the shift into a routine strategy against even marginal hitters. Then, when the rest of the league had adopted this "progressive" tactic, Maddon more or less retreated, using the shift less than any manager in the game last year. (While still maintaining an elite defense, one of the best we've ever seen, thanks in part to a number of factors harder for the competition to replicate.)

We point this out to note that articles like this one often start with a premise a given strategy is "good" or "bad" or "progressive" or "traditional." We will probably even use some of those labels in this article. But (A) context is everything, and (B) public perception of what's progressive is often outdated. Maddon's clubs remain selectively wild and innovative. The way Maddon's first baseman, Anthony Rizzo, charges sacrifice bunts, to my eye, is as aggressive and imaginative as anything any team is doing on the field. That this imaginativeness can coexist with "traditional" bullpen usage should tell us that "traditional" bullpen usage is not a moral outrage.

2. Braves

For example, it might seem unforgivable for a team like the Atlanta Braves, with a closer like Jim Johnson, to be as conventional as they've been. The Braves, while more respectable than they were last year, remain in basically rebuilding (or, at best, consolidation) mode. Rather than use this period to experiment with new processes, new philosophies, new personnel in new roles -- which they head-feinted toward last season -- they've run their campaign like a candidate with a 30-point lead in the polls: safe, boring.

For example, it might seem unforgivable for a team like the Atlanta Braves, with a closer like Jim Johnson, to be as conventional as they've been. The Braves, while more respectable than they were last year, remain in basically rebuilding (or, at best, consolidation) mode. Rather than use this period to experiment with new processes, new philosophies, new personnel in new roles -- which they head-feinted toward last season -- they've run their campaign like a candidate with a 30-point lead in the polls: safe, boring.

They gave the closer job to Johnson, a veteran with plenty of past closing experience but limited upside, declining velocity and fairly recent experience with being quite terrible. They've given him every save so far and used him almost exclusively in the ninth inning and in save situations. Nothing will be discovered from this. And while Johnson is signed through next season -- when the Braves might plausibly be good -- the nature of relievers in their mid-30s suggests he's a bad bet to be closing games for them in the 2018 postseason.

And yet, the Braves' hewing to tradition makes sense, and the sense that it makes speaks directly to the continuing reign of tradition: Johnson will probably be on the trade market this July, and the Braves know he'll be worth more if he's successfully closing. Because they've used him in a traditional manner, he has been protected as much as possible from uncertainty, irregularity or excessive demands. Coddling a closer like this might not be the very best way to win games, but it's probably the best way to win a Jim Johnson trade on July 31.

3. Rockies

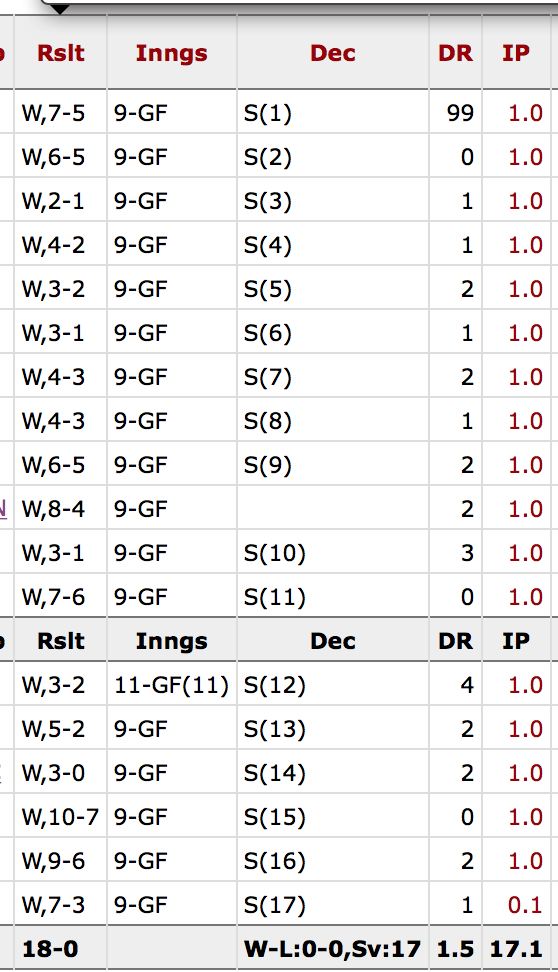

In all honesty, Greg Holland's game log is probably the most extreme picture of regimentation in the stack:

In all honesty, Greg Holland's game log is probably the most extreme picture of regimentation in the stack:

But I had less I wanted to say about the Rockies, so they're third.

The lefty setup man Jake McGee got one save, when the Dodgers sent two lefties and switch-hitter-but-better-against-righties Yasmani Grandal up in the ninth. I got excited thinking the Rockies were managing to the matchups, but nope. Holland was just unavailable that day.

4-6. Orioles, Royals, Phillies

These teams are lumped together mostly to demonstrate that, in the vast majority of cases, managers make their decisions based on roles more than on personnel. Remember when Buck Showalter didn't use Zach Britton with the score tied on the road in last year's wild-card game? He used, among other pitchers, Brad Brach instead? Of course you do. I've already linked to it three times in this article. Well, Showalter still wouldn't use his closer with the score tied on the road this year, against the Reds on April 20. His closer this year, though, is Brad Brach, the guy Showalter did use in the same situation last year. Brach had been the closer for exactly five days, after Britton went on the disabled list. He had one save on the season, four in his entire career. But on that day he was the closer, and the closer closes, so Showalter kept him out until the Orioles had a lead to protect.

These teams are lumped together mostly to demonstrate that, in the vast majority of cases, managers make their decisions based on roles more than on personnel. Remember when Buck Showalter didn't use Zach Britton with the score tied on the road in last year's wild-card game? He used, among other pitchers, Brad Brach instead? Of course you do. I've already linked to it three times in this article. Well, Showalter still wouldn't use his closer with the score tied on the road this year, against the Reds on April 20. His closer this year, though, is Brad Brach, the guy Showalter did use in the same situation last year. Brach had been the closer for exactly five days, after Britton went on the disabled list. He had one save on the season, four in his entire career. But on that day he was the closer, and the closer closes, so Showalter kept him out until the Orioles had a lead to protect.

See also the Royals, where Kelvin Herrera, after years as a setup man, is now the Royals' closer. He got the job by pitching so effectively in the seventh and eighth innings, but now that he's the closer he pitches the ninth, and only the ninth. Jeanmar Gomez, meanwhile, was the Phillies' closer until he wasn't. In the former role, he was kept out of games with the score tied. In the latter role -- which he got because he wasn't pitching well -- he pitches in the ninth inning of tie games on the road. It seems weird. It is weird. But we're pointing it out not to indict their managers but to demonstrate how central to bullpen strategy the role is. Not the pitcher. Not how good the pitcher is and what he throws and what his experience is, but the role he's in that day. We ignore managers' insistence on this philosophy at our own peril.

7-14. Giants, Mets, Diamondbacks, Yankees, Rangers, Twins, Brewers, Marlins

The bulk of teams remain here, or around here: mostly traditional, with an occasional surprise or a brief flirtation with something interesting.

When I profiled Andrew Miller this winter, he repeatedly brought up Dellin Betances as the throwback fireman who deserves more attention than he does. But even before he replaced the injured Aroldis Chapman in the closer's role, Betances was used like a pretty typical setup guy this year, only once bridging innings, never appearing before the seventh, and so on. He also has been wild, and his pitch counts have been high, which might have preempted any hope of using him the way Miller is used.

The Rangers might be slightly notable for how quickly they'll replace the guy in the closer's job. Sam Dyson learned the same lesson Shawn Tolleson did a year ago: It doesn't matter how good you were the year before, and it doesn't matter how "proven" you are. The Rangers will replace you in the second week of the season if you're bad.

The Diamondbacks might be slightly notable for how long they've let Fernando Rodney get bombed in the role.

The Marlins sort of promised to pull their starters more quickly and use their bullpen more in the middle innings. It's hard to say whether they have, or whether their starters have just been terrible. For what it's worth, their rotation leads the league in starts facing exactly 18, 19 or 20 batters -- in other words, pitchers who get pulled in anticipation of the crucial third time through the lineup. But it's not overwhelming statistical evidence. They've otherwise been so wedded to the traditional closer model that, in the absence of save opportunities, they've used their best reliever (A.J. Ramos) less than almost any other reliever on the staff:

Ramos: 13 innings, 2.77 ERA

David Phelps: 20 innings, 4.05

Kyle Barraclough: 17.1 innings, 3.12

Brad Ziegler: 16.1 innings, 6.61

Junichi Tazawa: 15 innings, 6.60

Dustin McGowan: 20.2 innings, 4.35

Nick Wittgren: 15.1 innings, 4.11

15. Tigers

They get this spot instead of being lumped in with the teams above based on one game: April 12, against the Twins. Manager Brad Ausmus was without his regular closer and his regular setup man that day. He sent Alex Wilson out to pitch the eighth, and, according to the game story, "while Wilson was working the eighth, Ausmus pondered whether Shane Greene or Anibal Sanchez would be his ninth-inning guy. But before he could make a decision, Wilson already had breezed through the eighth, and was the pick to go back out there." Wilson got the save. Nothing about that might seem all the important -- it was a weird day, with weird bullpen limitations -- but the fact that Ausmus went into a game, went into the eighth inning even, without a declared "closer" is notable.

They get this spot instead of being lumped in with the teams above based on one game: April 12, against the Twins. Manager Brad Ausmus was without his regular closer and his regular setup man that day. He sent Alex Wilson out to pitch the eighth, and, according to the game story, "while Wilson was working the eighth, Ausmus pondered whether Shane Greene or Anibal Sanchez would be his ninth-inning guy. But before he could make a decision, Wilson already had breezed through the eighth, and was the pick to go back out there." Wilson got the save. Nothing about that might seem all the important -- it was a weird day, with weird bullpen limitations -- but the fact that Ausmus went into a game, went into the eighth inning even, without a declared "closer" is notable.

They've otherwise been traditional. This is the median baseball bullpen usage in the year 2017: traditional, with a little weirdness once.

16. Blue Jays

In April, Joe Biagini pitched very well in something slightly resembling an Andrew Miller role, merging high-leverage and multiple innings. But it's not clear how intentional that was -- Biagini was nobody's idea of a relief ace entering the season -- and he has been moved to the rotation now. Otherwise, no surprises.

In April, Joe Biagini pitched very well in something slightly resembling an Andrew Miller role, merging high-leverage and multiple innings. But it's not clear how intentional that was -- Biagini was nobody's idea of a relief ace entering the season -- and he has been moved to the rotation now. Otherwise, no surprises.

17-19. A's, Mariners, Nationals

The term "closer by committee" actually covers two very different situations. In one, there's no good option, so the manager mixes and matches until somebody gets hot or the mess gets so hot an outsider is brought in. That's the Nationals, who have struggled along with a bunch of different closers but with mostly involuntary uncertainty. Manager Dusty Baker said as much in spring training: "I just noticed that closer-by-committee really doesn't really work."

The term "closer by committee" actually covers two very different situations. In one, there's no good option, so the manager mixes and matches until somebody gets hot or the mess gets so hot an outsider is brought in. That's the Nationals, who have struggled along with a bunch of different closers but with mostly involuntary uncertainty. Manager Dusty Baker said as much in spring training: "I just noticed that closer-by-committee really doesn't really work."

In the other, there's a whole bunch of good relievers, and a team shows willingness to use different closers on different nights depending on the matchups, the situation and which resources were burned up in the preceding eight innings. This is what the A's seemed to have, and they embraced it:

Along with (Ryan) Madson, Santiago Casilla has extensive experience closing. Sean Doolittle and John Axford are capable of the job as well. The A's also have a pair of more-than-capable setup men in Ryan Dull and Liam Hendriks. ...

"We'll have that conversation with the guys in the bullpen a little bit later on," [manager Bob] Melvin said. "Even when I do have the conversation with them, I don't know that there will be an exact science to that either."

After getting the first save of the season, Casilla spent a week pitching in the eighth inning. But this is the classic example of a fluid situation quickly becoming frozen: Casilla got his second save of the season on April 18 and hasn't done anything but close -- one-inning appearances only -- since.

That the A's stayed "fluid" for even two weeks is surprising. In most cases, the "committee" collapses upon the first successful save, whereupon whomever got that save gets the next and the next and the one after that.

The Mariners find themselves in a committee situation now, after Edwin Diaz lost the job. Tuesday was the first game under the committee plan. Steve Cishek -- just off the disabled list, having pitched the day before, and having lost the closing job last year -- got the first crack. ("He's been out there before," manager Scott Servais explained.) The Mariners had said they would play matchups and "use multiple relievers to piece together the ninth," but Cishek was allowed to face four batters, the first three of whom reached against him, two of whom were lefties, one of whom hit a winning home run. Nobody was warming up in the Mariners' bullpen.

Now, the Mariners relief corps was taxed, and not everybody was available that night. Going to Cishek and staying with him might have been the best move. On another night, the Mariners might really have used multiple relievers to piece together the ninth, like they said. More likely, though, that game was a glimpse at the actual reality: The Mariners have a closer, and they're going to use him like a traditional closer. They're just trying to figure out who it is.

20-22. Padres, White Sox, Pirates

Padres manager Andy Green hinted during the spring that he might try using an "opener," a reliever who would start the game before giving way to the "starter," thus preventing his opponents from loading up on lefties or righties. Was he serious? Probably not. The conversation was oddly coy, with lots of "said with a grin" in the recounting of it. Needless to say, the Padres have not done this. They have used their closer as the first choice in the ninth inning of tie games on the road though.

Padres manager Andy Green hinted during the spring that he might try using an "opener," a reliever who would start the game before giving way to the "starter," thus preventing his opponents from loading up on lefties or righties. Was he serious? Probably not. The conversation was oddly coy, with lots of "said with a grin" in the recounting of it. Needless to say, the Padres have not done this. They have used their closer as the first choice in the ninth inning of tie games on the road though.

Even after the Showalter/Britton debacle in last year's wild-card game, holding the closer back for a possible save remains the default. We count 61 games this year that had a tie score at the start of the bottom of the ninth; we count only 10 times when the closer pitched that inning. Generously, we might throw five more into the tally if we include "co-closers," or pitchers who were part of a committee at the time. Even with that, three-quarters of the time managers have opted to make the same move Showalter did.

The Padres, White Sox and Pirates have gone the other way, though not all the time. It's really not much, but there are arguably 19 other teams that have done less.

23. Cardinals

With Trevor Rosenthal pitching well again, the Cardinals have two qualified closers. They haven't used either one very imaginatively -- there was lots of winter talk that Rosenthal could be stretched out and work more like Andrew Miller, but stretching Rosenthal out in the spring led to problems. So, on the surface, the Cardinals have what lots of teams have: a closer (Seung-hwan Oh) and a setup man who is also really good (Rosenthal). However, by treating Rosenthal as slightly more than that, they've given Oh more rest than the normal closer gets. Oh has pitched three days in a row only once. Rosenthal, meanwhile, has collected three saves. A small thing, which is part of the point: We're at No. 23 and talking about really small things.

With Trevor Rosenthal pitching well again, the Cardinals have two qualified closers. They haven't used either one very imaginatively -- there was lots of winter talk that Rosenthal could be stretched out and work more like Andrew Miller, but stretching Rosenthal out in the spring led to problems. So, on the surface, the Cardinals have what lots of teams have: a closer (Seung-hwan Oh) and a setup man who is also really good (Rosenthal). However, by treating Rosenthal as slightly more than that, they've given Oh more rest than the normal closer gets. Oh has pitched three days in a row only once. Rosenthal, meanwhile, has collected three saves. A small thing, which is part of the point: We're at No. 23 and talking about really small things.

24. Angels

There was a point early in the season when Cam Bedrosian was pretty obviously Mike Scioscia's closer, but Scioscia wouldn't say it, and then you'd look down at the bullpen and see Bedrosian warming up in the seventh inning, and you could see why Scioscia wouldn't say the word "closer." It let him use Bedrosian in the seventh if he needed to. Or the ninth if he wanted to. This is really the secret to using a closer flexibly: avoid saying the word. Scioscia would call him "the lead dog," which everybody knows means the same thing, but the language of these things matters.

There was a point early in the season when Cam Bedrosian was pretty obviously Mike Scioscia's closer, but Scioscia wouldn't say it, and then you'd look down at the bullpen and see Bedrosian warming up in the seventh inning, and you could see why Scioscia wouldn't say the word "closer." It let him use Bedrosian in the seventh if he needed to. Or the ninth if he wanted to. This is really the secret to using a closer flexibly: avoid saying the word. Scioscia would call him "the lead dog," which everybody knows means the same thing, but the language of these things matters.

Anyway, then Bud Norris became the closer and everything is back to being totally uninteresting.

25-27. Rays, Red Sox and Dodgers

Closer Alex Colome has come into the eighth inning of a save opportunity five times already. Kenley Jansen has done so four times for the Dodgers. Craig Kimbrel has entered one save situation in the eighth and entered with the score tied in the eighth. The year Francisco Rodriguez set a record with 62 saves, he didn't pitch in the eighth inning even once.

Closer Alex Colome has come into the eighth inning of a save opportunity five times already. Kenley Jansen has done so four times for the Dodgers. Craig Kimbrel has entered one save situation in the eighth and entered with the score tied in the eighth. The year Francisco Rodriguez set a record with 62 saves, he didn't pitch in the eighth inning even once.

Through teams' first 35 games this season, there have been 28 saves of four outs or more. That's the most (in the first 35 games of a season) since 2007, seven more than last year and double the number we saw in 2014, 2013 and 2012. It's not a big difference in raw numbers, but it falls under our purview today.

It's worth wondering whether Colome is pitching in this more aggressive closer mode for the same reason Johnson of the Braves isn't: to boost his trade value. While the Braves might just love to get to the deadline with Johnson still looking like a plausible closer, the Rays might be positioning Colome to be this postseason's Andrew Miller or Kenley Jansen: multiple innings, extended saves.

28. Indians

We keep talking about teams using, or not using pitchers like the Indians use Andrew Miller, but it was, of course, an open question whether the Indians would once again use Andrew Miller like Andrew Miller. They obviously wouldn't use him the way they did in the postseason, when all questions of fatigue and stamina and pacing get tossed out. Would they use him the way they did last summer, bringing him into tight spots early in games and to bridge innings, as a less-established reliever would expect to be used?

We keep talking about teams using, or not using pitchers like the Indians use Andrew Miller, but it was, of course, an open question whether the Indians would once again use Andrew Miller like Andrew Miller. They obviously wouldn't use him the way they did in the postseason, when all questions of fatigue and stamina and pacing get tossed out. Would they use him the way they did last summer, bringing him into tight spots early in games and to bridge innings, as a less-established reliever would expect to be used?

The answer is yes, with two caveats. As for the yes: Miller has already made six appearances that bridged innings. When he was the Yankees' setup man last year, he did this only twice, over about double the time period. He is averaging more than an inning per appearance, which he told me is something he keeps an eye on with pride. Thanks to this -- and to how well he has pitched -- he's fourth among all relievers in win probability added, despite appearing in the ninth inning only once.

As to the two caveats: Four of his past five outings have been three-out jobs in the eighth inning, the sorts of outings that regular setup men do in their regular setup jobs. So he might be slowly falling into a more orthodox setup role. More disappointing, though, is how little his presence has affected the way the Indians use their closer Cody Allen. Having Miller around should free them up to use Allen more expansively, knowing that if he pitches two innings one night, Miller will be there to carry the load the next night. The opposite has happened: Allen has been asked to get four outs only once. On the other hand, it's a long season.

29. Astros

The more pressing Andrew Miller question wasn't whether the Indians would use Andrew Miller like Andrew Miller, but whether Andrew Millers would pop up all over the place. Mostly, no. In Houston, yes, where Chris Devenski has thrown 24 innings in 14 games, appearing in close games as early as the fifth, throwing as many as four frames in an outing, collecting two saves, and pitching in extremely high-leverage situations. (Higher, even, than Miller has this year.)

The more pressing Andrew Miller question wasn't whether the Indians would use Andrew Miller like Andrew Miller, but whether Andrew Millers would pop up all over the place. Mostly, no. In Houston, yes, where Chris Devenski has thrown 24 innings in 14 games, appearing in close games as early as the fifth, throwing as many as four frames in an outing, collecting two saves, and pitching in extremely high-leverage situations. (Higher, even, than Miller has this year.)

Devenski and Miller aren't alone. Mostly they are, but not entirely. There have been 46 outings this year in which a reliever has recorded five or more outs in a high-leverage situation in the ninth inning or earlier. Or, in other words, there have been 46 outings that resembled the old "fireman" outings. There were 33 during the first quarter of last season.

There's also their closer, Ken Giles, who has twice come into games in the eighth and then given way to other pitchers. Once, it was because Mike Trout and Albert Pujols were coming up; Giles got through them and let Will Harris face the bottom of the order in the ninth. The other time was also interesting:

The Astros were trailing 5-4 in the top of the eighth, and manager A.J. Hinch decided to get Giles warm and use him in the bottom of the inning. The Astros scored four runs while Giles was warming up, and now it was a save situation. Hinch stuck with his plan -- Giles pitched, got the hold, then gave way to Luke Gregerson.

"[Hinch] has said since spring training he reserves the right to use Giles in high-leverage situations ahead of the ninth inning," the game story reported. "'I've said time and time again I don't really care what the order is. Ken's still going to finish most of the games. But that's what I mean by 'most of the games.' "

30. Reds

The committee that actually stuck. Four relievers have saves for the Reds, and while Raisel Iglesias is clearly the closer (with seven saves), the "committee" has made it possible for the Reds to do all sorts of fun things with him. He has three six-out saves, which is almost unheard of from closers, because managers don't want to be without their closer the next day. On April 15, he entered a game in the fifth inning, pitched two innings and got the win; Michael Lorenzen ended up with the save.

The committee that actually stuck. Four relievers have saves for the Reds, and while Raisel Iglesias is clearly the closer (with seven saves), the "committee" has made it possible for the Reds to do all sorts of fun things with him. He has three six-out saves, which is almost unheard of from closers, because managers don't want to be without their closer the next day. On April 15, he entered a game in the fifth inning, pitched two innings and got the win; Michael Lorenzen ended up with the save.

In 15 games, Iglesias has thrown 21⅓ innings. That's more than 40 percent more innings than appearances. In the past decade, only three pitchers have collected 20 or more saves while throwing even 20 percent more innings than appearances. In two cases, the relievers racked up innings in very different roles before or after closing: Jenrry Mejia started seven games, Alfredo Aceves lost the ninth-inning job and worked in long relief to close out the season. The third, Andrew Bailey, threw 55 innings in 48 appearances after taking over as closer.

Which all means this: Raisel Iglesias is new. What the Reds are doing is new. This is new. It might not last, but for now we can say that 2017 is not all more of the same. Whether or not bullpens are changing, this bullpen has changed.